This article was originally published in The Examiner on September 14, 2017.

By Eleanor Skelton

Staff Writer

Rumors rose almost faster than floodwaters during the aftermath of Hurricane Harvey.

Southeast Texans reshared social media posts claiming that flesh eating bacteria was lurking in floodwaters, animals lost during the storm were being euthanized at Ford Park, and FEMA was requiring that homeowners place signs on debris removed from flooded homes forbidding its removal until the debris was documented.

All untrue.

When Beaumont woke up to no water after the city lost service from the main pump station in the early morning hours of Aug. 31 after officials previously said that water would not be shut off on Aug. 29, panic spread throughout Mid-County and citizens overwhelmed emergency dispatchers, calling to ask if they would be next to lose water.

Officials in Port Neches, Nederland and Groves tried to assure residents that there were no plans to shut off water in any of those cities, according multiple statements released to the media.

“Mid-County Central Dispatch Center is being inundated with calls regarding various rumors regarding Tropical Storm Harvey and its aftermath,” Nederland Police Chief Darrell Bush said in a release.

The City of Port Neches also cautioned residents against listening to unsubstantiated rumors on social media because they said the higher call volume is “causing major difficulties” when first responders and the dispatch centers are having to answer calls to “dispel these rumors.”

Similarly, controversy swirled around the grassroots volunteer efforts organized at Jack Brooks Airport.

Jolei Shipley, who had helped organize supplies for airlift and bus evacuees, told The Examiner she was concerned humanitarian aid supply lines were being interrupted Sunday, Sept. 3.

She and other volunteers working with her received aid from Operation Air Drop and the Sky Hope network, a group of volunteer pilots. Over 200 aircraft flew over 500 missions bringing in supplies when the flooded roads were impassable, Operation Air Drop co-founder Doug Jackson said.

Then Shipley and her band of volunteers gave toiletries, cleaning supplies, formula, diapers, clothes, water and other supplies to a list of about 15 nearby churches that distributed to the community.

Jackson said that the operation in Texas was unprecedented.

“We’ve been told that it’s the largest response to a natural disaster in the history of private aviation,” he said, explaining that the group has now been contacted by the White House to help with Hurricane Irma relief.

Shipley explained that her operation was efficient: a four-hour turnaround time between supplies being delivered to putting them in people’s hands, with the help of American Airlines employees and nine National Guard men helping direct air traffic and unload.

“Yesterday and today, I had it off the plane, some in two hours from an airplane out of Austin to a distribution center, most within four hours,” she said. “All volunteer run, we have got no funding from anybody.”

Several of the distributing churches were within walking distance of flooded areas, Shipley said.

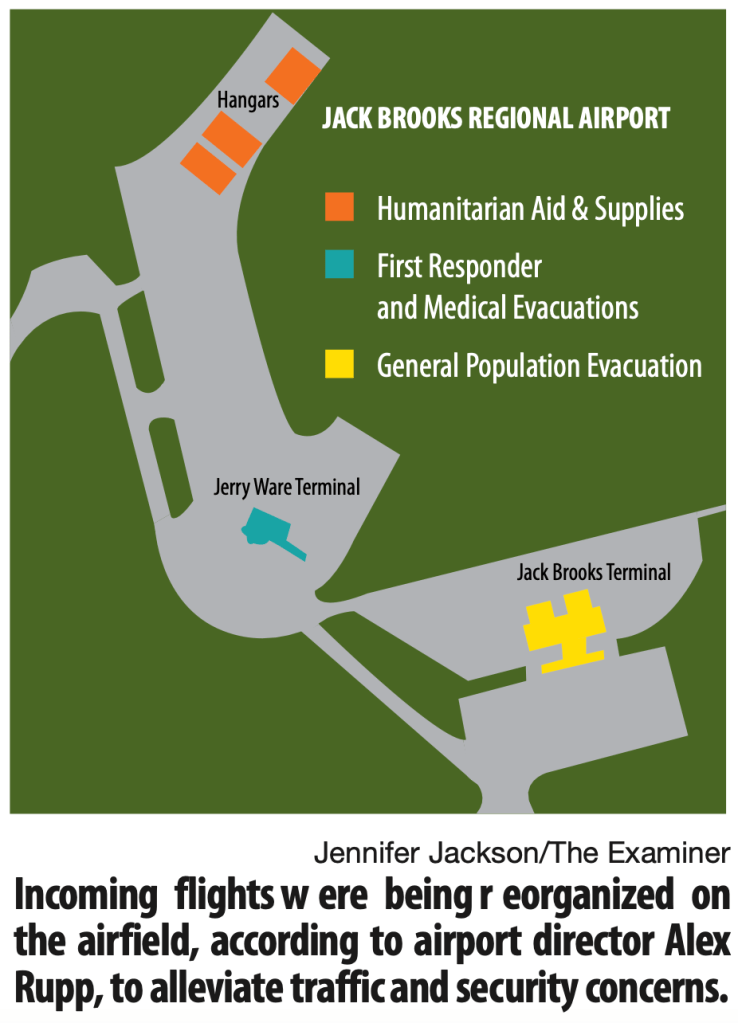

Incoming flights were being reorganized on the airfield, according to Jack Brooks Airport Director Alex Rupp. Shipley said that she feared that this shift would leave churches without supplies for flood victims and donated clothing left in the Jack Brooks terminal would be thrown out and wasted.

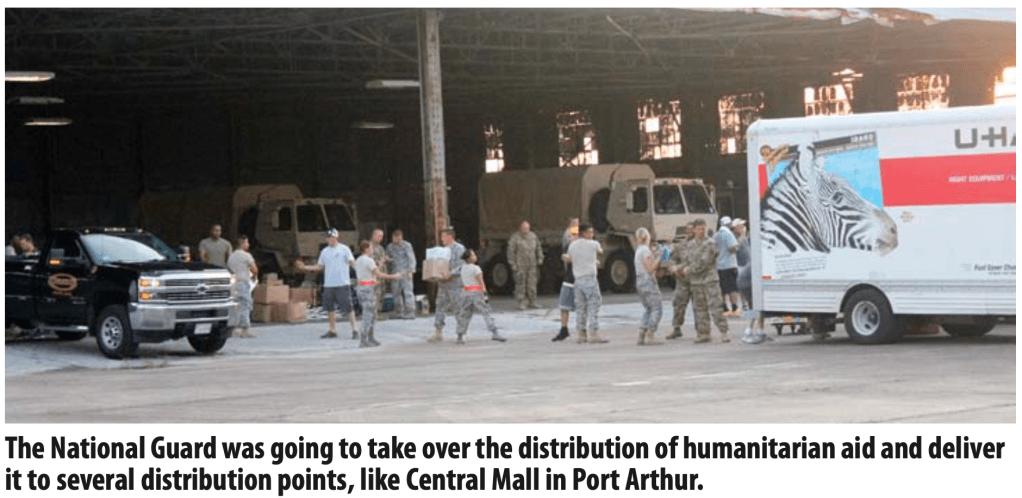

According to Shipley, officials told her that the National Guard was going to take over the distribution of humanitarian aid and deliver it to several distribution points, like Central Mall in Port Arthur.

Keith Bass, a volunteer who organized boat rescues in West Port Arthur, Vidor and Lumberton using Boss Burger on Boston Avenue as a staging area and the Zello walkie talkie app, also expressed concern that the National Guard, Red Cross and government officials had co-opted volunteer efforts.

His rescues had been “all civilians, no city officials” and he felt that regulating distribution was “shocking and very disturbing.”

Shipley said that her volunteer group was disbanded without a clear transition.

“We’ve been asked to leave the airport. I don’t have access to any additional supplies,” she said on Sept. 3.

“I got six pallets of water out there last night, between 10 p.m. and midnight,” Shi-

pley said, talking about Diamond D on Highway 90. “They called me three hours ago, they’re out of water, they can’t find water, they can’t find anything.

“I was their sole supply.”

But County Judge Jeff Branick said Sept. 3 that supply lines were not being

cut off, just redirected.

“We’re not stopping the receipt of air assets,” he said. “We’re going to continue to push out to the points of distribution that are scattered in the counties and the cities.”

Volunteers gathered around Shipley in the terminal said it was unclear how the churches would replenish their supplies and if they could go to the official distribution points.

The Pentecostals of Nederland was one of the organizations listed as receiving aid from the airport, according to Shipley.

“We’ve just been in contact with other churches within our organization,” DesaRae Monroe, a volunteer with Pentecostals of Nederland, said Sept. 7. Monroe explained that her church is part of the United Pentecostal Church International, a larger denomination, which has also been organizing hurricane relief efforts.

Pathway Church in Nederland was another distribution site on Shipley’s list.

“We never really depended on them at all,” Pastor Caz Francis aid. “Most of our supplies did not come from the airport,” Pastor Caz Francis said.

Much of Pathway Church’s relief aid came from out of state and other churches and friends located in Texas.

Beaumont Fire Department District Chief Eric Chapman, who was in charge of all distribution points in Beaumont during the relief efforts, advised churches and other organizations to make special requests through the Emergency Operations Center.

According to Chapman, churches were able to receive aid through local government points of distribution (PODS).

Jack Brooks Airport Director Alex Rupp addressed some of the volunteers’ concerns.

“This was a very chaotic situation,” Rupp said, explaining that 800 to 1,000 evacuees were in the Jack Brooks Terminal waiting to be flown or bused out of town at one point.

He and his team reorganized flights so that all general population evacuations like flood victims went out of the Jack Brooks Terminal, first responders and medical evacuations were in the Jerry Ware Terminal, and humanitarian aid went to hangers on the side.

Rupp says about 3,500 people were evacuated, with 2,112 leaving on an aircraft in addition to 180 medical evacuations by air.

“Our main job was to be sure that this airfield flowed correctly. We wanted to be sure all that happened safely,” he said, explaining that airplane crashes have a higher fatality rate than automobile accidents, and one accident would further hinder more supplies coming in and tie up limited resources.

Airport personnel did not tell volunteers to leave the airport or stop incoming aid, Rupp said. He did say that he locked the back door of the terminal after evacuees and volunteers cleared out because this violated TSA security standards, he explained.

“Those clothes [left in the terminal] are not going to get thrown away,” he said. “We’re going to make sure those goods go to wherever they need to go to.”

Airport officials believe that better communication could prevent another situation like this.

“When a disaster like this comes through again, and we have volunteers coming through the airport, they need to go through the proper channels and follow protocol and check in with airport administration,” Jack Brooks airport secretary Heather Ripley said.

Shipley and her volunteers later reorganized at the Beaumont Municipal Airport, located near Highway 90. Their last delivery came in Sept. 10, she said.